shoulder instability-part II

Good to have you back for the second and final part on Shoulder Instability!

On this page we will look at Instability with relation to lesions of the Labrum and Rotator Cuff.

So imagine your on a placement, or working as a graduate physio, and a patient comes to you with shoulder complaints. This time there is a history of a traumatic event (such as a Fall On Out Stretched Hand – FOOSH), or maybe they’re an over head sporting athlete… or perhaps they are 40+ reporting an insidious onset of shoulder weakness.

We first want to narrow things down with an anamnesis, and from this we should have a good idea if the issue is from overuse, disuse, misuse or abuse. Knowing which will help form your hypothesis.

So many times I’ve heard top named physicians/physiotherapists say ‘the diagnosis is nearly always in the anamnesis’. Performing a good anamnesis is an art. From it, you can create a main hypothesis, with some other suspected pathologies following close behind.

The Shoulder Evaluation will be covered in the next section, but what good is an evaluation if we don’t know about the ‘issues in the tissues’ we’re testing. Understanding the structural damage will help us understand how the tests work.

LABRUM TEARS:

Labrum; from the latin ‘labium’ meaning a lip-shaped anatomical edge/rim or structure.

With labral injuries you are likely to hear complaints of pain during certain OH activities such as pitching or volleyball, a feeling of instability, events such as a shoulder dislocation, or painful popping or clicking sounds (different to simply clicking a joint, as these can be reproduced immediately by repeating the movement!). These are very clear signs and symptoms of a labral tear.

To understand this pathology, first we must learn a bit about the tissues structure and function:

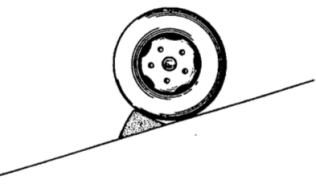

The glenoid labrum is a dense fibrous rim (containing some elastic fibers) with a peripheral blood supply which decreases with age. It serves to deepen the glenoid fossa (by 50%), and is an attachment site for the GH ligaments. It provides passive stability to the shoulder joint in the same way this ‘chock’ would provide passive stability to a car:

The labrum functions in combination with compressive forces to stabilize the joint especially within the midrange of GH motion, where the capsular ligament structures are lax (Wilk et al. 1997).

The labrum functions in combination with compressive forces to stabilize the joint especially within the midrange of GH motion, where the capsular ligament structures are lax (Wilk et al. 1997).

An interesting fact is that the superior labrum attachment is loose, and can produce similar movement as seen in the meniscus of the knee. In contrast to this, the inferior part of the labrum is firm, and does not move (O’Brien 1994).

So why would the shoulder need so little fluid? Well, this limited amount helps provide a ‘syringe type suction’ of the humeral head into the glenoid fossa. Knowing this, it is understandable that when the capsule is pierced, possibly following a labral tear, this would allow extra-capsular fluid inside… and negative pressure will be lost! This reduces glenohumeral passive stability… leading to an increased risk of (sub)luxation.

Some studies found that by venting a shoulder capsule (allowing fluid in), forces needed to translate the humeral head reduced by 55%, and in movement an increase of approximately 50% anteriorly, posteriorly and 60% inferior translation being the worst (Wilk et al. 1997). – The predominant inferior translation was most likely due to the ‘recessus axillaris’ or ‘axillary pouch’ of the inferior capsule (pictured below).

Interesting fact: In a healthy GH joint, the capsule is sealed airtight which enhances stability with a negative intraarticular pressure. Its surprising to know that normally there is very little fluid in a capsule….less than 1ml! (Matsen 1990). I found this quite surprising as some literature drawings show a joint with quite an enlarged capsule, leading you to believe it contained lots of synovia for the humeral head to ‘swim around in’. Have a look at the video and picture below showing the tightness of the capsule.

Video showing rotator cuff and capsular movements on a cadaver:

You can see its really air tight! This image from Aclands also shows the capsule once the rotator cuff muscles have been removed.

Types of Labral Tears:

Basically these each differ depending on the mechanism of injury. There are many various types and names given (SLIP, SLOP, SLAP, HAGL, BHAGL, Bankart, GLOM, GLAD, GARD …I could go on). Don’t be put off by it all, each is simply an exotic combination of labral, capsule, periosteal and cartilage damage along with some avulsion fractures. Labral tears can occur from trauma or repetitive stresses. The abbreviations all sound very fancy, and they give important information to the MRI/Arthroscopy clinician…but we only need to know and understand the area of instability and damage, so we can tailor our treatment with an understanding of how the humeral head affects surrounding tissues in move movement (covered more in treatment section).

As you can imagine, most of these trauma injuries happened at a certain ‘time‘ of your ‘shoulder clock’… Meaning the (repetitive) traumatic translation or dislocation occurred (in most cases) in one direction. (picture taken from Radiologyassistant):

So we don’t need to memorise each and every one… but we do need to where the damage is, what happened (overuse/misuse/abuse?), to better realise the implications for rehabilitation.

The main problem in all of these is related to the labral detachment and associated loss of tension in the glenohumeral ligaments. These can be the cause of pain in end ranges and instability (mostly unidirectional as mentioned in part 1).

As this is not a ‘know it all’ article on the topic, we will take the 3 most common occurrences:

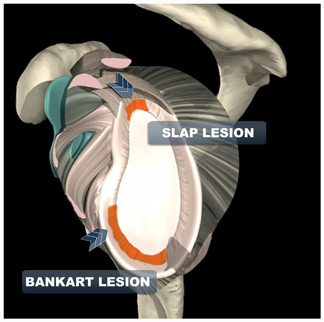

- SLAP Lesion (superior)

- Bankart Lesion (inferior – anterior)

- Reverse Bankart Lesion (inferior – posterior)

Knowledge of each is enough at this stage for you to feel strong at the knees when your supervisor/manager passes this type of patient to you.

1. SLAP Lesion (Superior Labrum from Anterior to Posterior)

SLAP lesions can be caused by either a single traumatic incident, or by degeneration/overuse/attrition.

– Trauma:

A single traumatic even causing a SLAP lesion can occurring during contact sports when arm tackling in football/rugby (depending where your from ;)) or from general incident trauma such as a FOOSH, bracing your arm in a motor accident, or any large sudden force applied to the arm which would drive the humeral head upwards.

– Degeneration/Overuse/Attrition:

Say hello to Mr Slap. If theres one guy who has abduction, extension and ER… its this guy! He is definitely making use of his joint end ranges here, although looking a little closer we can notice the hyperextension of the spine which help in giving him that extra ROM. Notice also that this extreme range of abd, ext and ER, is an ‘at risk’ position for Internal Impingement.

A quick fact: Over head (OH) athletes with an increase of ER nearly always present with a Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit (GIRD). However, if you take the total rotation motion and combine ER and IR measurements, the numbers are almost identical. So is ‘GIRD’ something to worry about when your total ROM is still 180?

When looking at SLAP lesions, its important to know a large portion of the long head of the biceps originates from the top (superior) portion of the labrum. OH sports can apply significant stresses at this attachment site. This can eventually lead to tearing of the biceps off of this attachment. OUCH. This is a type 4 and most serious (shown below).

If your looking at an overuse injury here, you can consider OH athletes especially racquet sports, sports requiring throwing (baseball, cricket) and swimmers (especially front crawl, back stroke and butterfly swimmers). Studies have found more than 40% of elite swimmers complain of shoulder pain at some point with most of their pain being due to instability (Weldon 2001). OH athletes are also prone to stress on the passive stability structures (ligamentous labral complex) and dynamic stability components (rotator cuff musculature).

Are all SLAP lesions the same?

I know classifications can be boring, tough to read and tough to remember, but lets go into the classifications of this one just to give us an idea of how a single type of lesion can vary:

This is the classification system for SLAP lesions (image by ubc medical art):

Type-I SLAP lesions consist of degenerative fraying on the inner margin of the superior aspect of the labrum.

Type-II SLAP lesions (the most common), involve the biceps attachment and the adjacent superior aspect of the labrum being pulled off the superior glenoid tubercle.

Type-III SLAP lesions have a superior labral ‘bucket-handle’ tear.

Type IV SLAP lesions have a superior labral bucket-handle tear that extends Into the biceps tendon.

So are all of them tears? Nope, the first is attrition (wear and tear) of the superior labrum. Meaning someone could have a SLAP injury causing them pain… but there is no ‘tear’. Type 2-4 could be a progression from this degeneration/overuse/attrition, or caused by a single traumatic incident.

Especially if your going into sports physiotherapy, the phases of movement involved in throwing a ball or taking a forward stroke when swimming are important to know… infact they’re essential. Here is the motion divided into 3 parts:

– CockingThis motion involves abduction, ER and extension (stresses the anterior inferior labrum as in a Bankart). The muscles involved are the posterior deltoid, infraspinatus and teres minor. In this position the joint is at risk of anterior subluxation (typical for a Bankart Lesion) because the humeral head is in a position which is pressing against the already stretched anterior and inferior capsule. There is also a risk of infraspinatus strain if movement is explosive (think of the forced ER).

– Acceleration

This is the main phase and is linked to performance. The muscles involved are the anterior deltoid, pec. major, latissimus dorsi, subscapularis and the teres major (the internal rotators).

This is the main phase and is linked to performance. The muscles involved are the anterior deltoid, pec. major, latissimus dorsi, subscapularis and the teres major (the internal rotators).

Mechanism of action:

The combined superior Pulling Direction + Maximum Contraction + Repetition can =Rotator Cuff Attrition. (mainly the supraspinatus and biceps brachii tendons).

Why damage to the supraspinatus and biceps brachii if they are not in use?

It is similar to the superior translation described in the impingement article. However, this time the movement begins in maximal flexion… and is going into adduction… in a performance situation.

Performance situations involve large compressive forces during movement. When you combine this with muscle fatigue/altered biomechanics/improper muscle recruitment or simple overuse… passive stability fails and structures are damaged.

When the humerus goes past a certain angle in ‘adduction’ in relation to the glenoid plane, the compression and combined pulling direction cause a superior glide of the humeral head… add some repetition of this and you have a SLAP recipe.

Note: The human body is extremely tough and adaptive, but we were not created with over head sports in mind! So you could say this is a combination of ‘overuse’ and ‘misuse’.

– Following through

During this phase the infraspinatus and biceps work eccentrically with the biceps, another possible cause of shoulder soreness. Posterior labral strains can occur at this time, putting the joint at risk of posterior subluxation (risk of Reverse Bankart Lesion).

During this phase the infraspinatus and biceps work eccentrically with the biceps, another possible cause of shoulder soreness. Posterior labral strains can occur at this time, putting the joint at risk of posterior subluxation (risk of Reverse Bankart Lesion).

You could throw this example back into my Impingement section, as studies have shown the primary causes of shoulder pathology in OH athletes involves SLAP and internal impingement(Jazrawi et al. 2003). It was also found that OH athletes tend to develop anterior capsule laxity, and posterior capsule contractures (Labbe et al. 2004). Internal impingement can result secondary to these capsular changes (Imhoff et al. 2000). With that being said… if your tests show a shortened posterior capsule with anterior laxity, along with pain in abduction, ER and extension… that could be an indication for internal impingement.

For more on throwing, heres a good article on ‘The Kinetic Chain in Overhand Pitching‘.

For a great slow motion video of world champion pitcher Tim Lincecum click here.

For a great slow motion video of world champion pitcher Tim Lincecum click here.

2. Bankart Lesions (Anterior Dislocation)

The shoulder is designed for mobility, this makes it very useful for ROM, however its the reason why it is infamously the most dislocated joint in the body!

Anterior instability is the most common type of instability, representing approximately 95% of all shoulder instabilities and dislocations. Anterior dislocations are mainly caused by an abduction, extension and ER movement (sound similar to the ‘cocking’ part of the previous section?). A Bankart lesion is a lesion of the inferior-anterior part of the glenoid labrum, this injury can be caused by repeated anterior shoulder luxations and subluxations (not all the way out). An anterior dislocation of the shoulder joint can also damage the connection between the labrum and capsule which would be a Humeral Avulsion of the Glenohumeral Ligament HAGL . The HAGL abbreviation basically means that part of the GH capsular ligament has been pulled off, close to the humeral head (video of this below).

Bankart Lesions usually are due to an absence (approx 27%) or a poorly constructed medial GH ligament. These lesions are more from a traumatic event rather than repetitive movements. This explains why a Bankart Lesion is usually part of the ‘anterior dislocation package deal’.

If your patient was unfortunate enough to get the package deal, it would involve a degree of inferior-anterior labrum-glenoid separation. If its a ‘Bony Bankart’ then you can expect the glenoid rim in this region to also be fractured. To add to the existing problems, labral tears can mean extra-capsular fluid may enter (as previously mentioned). This along with the labral damage means 2 passive stability factors are reduced, making the shoulder more susceptible to future dislocations.

Unfortunately thats not all, can you guess what other injury can come with an anterior dislocation?

… a Hill-Sachs lesion. This is a ‘dent’ fracture to the posterior humeral head. This only occurs in dislocations when the humeral head impacts against the front of the glenoid by external force. As you can imagine, the depth of the ‘dent’ reflects the amount of damage to the anterior capsule and labrum. Therefore, larger Hill-Sachs lesions mean there is a higher risk for a repeat dislocation, due to passive stability damage.

Feeling like a surgeon yet?

And a picture of a Bankart compared to SLAP lesion:

3. Reverse Bankart Lesion (posterior dislocation)

The last one! We won’t spend too much time here are the concept is basically the same. Posterior dislocations cause… you guessed it, posterior labral tears. Which are given the name… Reverse Bankart Lesions.

Posterior labral tears are less common, but sometimes seen in athletes with the condition explained in my Impingement article: ‘Internal impingement’. This time though, the rotator cuff and labrum are pinched more in the back of the shoulder. Its nice to see how things are all inter-related hey?

Reverse Bankart Lesions are the most common attritional labral tears

As mentioned before, a labral ‘tear’ doesn’t have to be a ‘tear’. The name is commonly used for ‘fraying’ or a detachment of the glenoid labrum from the bone. If you fell down and your arm dislocated… then the humeral head is what transfers the force to the labrum, pushing it off of the glenoid. Reverse Bankarts are usually from repetitive stresses in OH athletes such as pitchers orvolleyball players, where the biomechanics differ.

Summarising Labral Lesions:

Know that these injuries come mostly within sport and traumatic falls. Many do not need require surgery unless needed for a return to sport, not all cause pain, it is more stability and mechanical problem which are the issue.

ROTATOR CUFF LESIONS

So is a rotator cuff tear ACTUALLY a tear? Funnily enough… most times its not! As with many musculoskeletal problems, rotator cuff pathology can stem from a single traumatic event, or be a slow degenerative process.

Most RC problems are degenerative, so risk increases with age. Whether degenerative or by trauma, the issue involves one or more of the four rotator cuff tendons in the shoulder being affected.

So lets divide the rotator cuff tear into two:

1. Atraumatic – Mostly degenerative.

2. Traumatic – Following a significant injury or fall.

Atraumatic:

The most common cause of a rotator cuff tear is degeneration (tendinosis). This is from gradual wear of the tendon material combined with a poor blood supply plus prolonged (and sometimes intense) loading. As a result, these issues are more common in older patients and can become larger with time. These patients do not report any injury to their shoulder, the insidious onset creates the story that ‘it gradually started hurting then became weak’.

Of course a sudden trauma and strain can speed up this process, but the trauma is usually more mild (such as picking up a heavy suitcase with the arm fully extended out in front of them), maybe with a ‘pop’ feeling… and typically the patient will report some pre-existing (mild) rotator cuff symptoms.

Like mentioned in labral tears, just because something is torn, does not mean it needs to be fixed! MRI is the gold standard for RC tears, if only a small tear (and not from trauma or a serious injury) then conservative treatment is recommended. Many people live with tears of their rotator cuff and do not even know they have one!

Traumatic:

Traumatic tears are far less common then degenerative tears, but usually more symptomatic. In this case, your patient had healthy tendons which are torn due to a traumatic event. This result is from an abrupt failure of the tendon, typically at its insertion into the humeral head, but occasionally within the mid tendon.

So whats the likely story?

Your patient may describe falling on their side, and then finding they can not move their arm due to pain and weakness. Movements can also include rapid twisting motions of the shoulder (Internal or external GH rotation) or shoulder dislocations in patients over age 40.

What happens to the muscle after the tear?

As our muscles are under tension, if a tendon is torn on one end, it will start to retract or pullback towards the other end. If you have a large tear, your rotator cuff tear can retract significantly, this will affect function causing it to atrophy like any other muscle. Traumatic tears are treated differently then degenerative tears. These injuries are typically treated with surgery asap.

Depending on the tear, many will respond to physiotherapy, yet some may not.

Take home message:

If your patient has a degenerative RC tear and did not suffer a significant injury, if it is small and not affecting function, physiotherapy could and should be indicated as their primary treatment!

EXTRA: Posttraumatic Arthritis (PA)- What do you know about it?

Post-traumatic arthritis happens after a significant trauma is sustained by the joint, ruining the cartilage. This could be the result of a car accident or after repeated trauma. Since shoulder injuries are common due to the shoulder joint’s instability, injuries such as shoulder fractures and shoulder dislocations may lead to PA. Sporting injuries and other accidents can also cause this condition. PA symptoms may include having fluid in the joint, as well as pain and swelling.

Congrats! Thats Instability done.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário